John 16:21 gives us the heart of Jesus’ understanding of his work on the cross and tomb as expressed in the Gospel and letters of John. That’s why I have chosen the alternative Gospel reading for today. I can never pass up an opportunity to talk about Jesus and childbirth!

This is my last sermon for a few weeks, as I am about to head off on a combination of annual leave and study leave. I usually send out my Sunday sermons on Saturday morning for St Paul’s people who won’t be able to get to church, and also for my clergy friends who might have had a particularly hard week and be in need of sermon ideas. Please make use of anything that is useful for you and leave anything that is not.

You will continue to receive emails in the Faith of our Mothers series each Tuesday.

“When a woman is in labour, she has pain because her hour has come. But when her child is born, she no longer remembers the anguish because of the joy of having brought a human being into the world.”

These are the words at the heart of Jesus’ self-understanding in regard to his ministry. He understood his calling to be about childbirth – with all the danger, all the pain, all the mess and, in the end, all the joy.

Anyone who has ever been in a labour ward knows the truth of these words. The whole process is full of the highest and lowest emotions.

Some pregnancies are longed for and prayed for – maybe almost despaired of before they finally take place – and so are met with celebration. And morning sickness.

Some pregnancies are discovered with dread and dismay.

And there are all manner of possible reactions in between. Pregnancy and childbirth is always momentous and lifechanging for the family in which they occur, and especially for the woman in whom they occur. Momentous in themselves and also accompanied by a tidal pull of complex emotions because of the hormones that course through our veins through those months of pregnancy and early years of new life.

The Gospels present Jesus as probably the eldest in a large family, who would therefore have been very close to his mother, Mary, through the pregnancies and births of his younger siblings. Of course, some Christians believe Jesus was the youngest in his family, and that Mary did not give birth again, and even in that case Jesus still would have become acquainted with the processes of pregnancy and childbirth as his older half-siblings became parents.

As the youngest sibling in my family, I have been an aunty since I was nine years old, and learned a lot about caring for babies by practicing on many, many nieces and nephews. Even so, I have never been present at the birth of a child other than my own. In our world, the painful, messy, dangerous realities of childbirth are usually hidden from view in clinical, sterile, professional medical settings. There is a lot to be said for that, of course, in the resulting low maternal and infant mortality rates in Australia.

The realities of first century pregnancy and birth were completely different, especially for the vast majority of families living in single-roomed houses with no possibility of privacy.

Birth happened at home, with no pain relief. The cries of agony and fear would have been heard by the whole family and the whole neighbourhood, for as long as it took for the birth to be completed. The risk to the mother and the baby were huge, and the children of the family would be listening and offering their mum what support they could, and would have known full well that this agony might be leading to a strong, healthy baby sister or brother in their mother’s joyful arms; or it might not.

In their community they would have seen other outcomes. Babies not surviving. Mothers not surviving. Without surgeons to repair the damage done to the mother’s body after complicated births, women might survive but with wounds that left them unable to function or maintain their place in the community.

I have spoken about this at length, and probably made you uncomfortable, because I know that when you hear of a man talking about the pain and fear involved in childbirth you might think he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. But if you imagine a son, who loves his mother deeply, watching and hearing his mother endure this life-threatening procedure every other year, perhaps, throughout his childhood, and hearing the other women in the village, and seeing labour sometimes end beautifully and sometimes devastatingly, then we can believe that Jesus knew exactly what he was talking about when he approached crucifixion with the metaphor of childbirth dominating his thinking. Just like a woman giving birth to a baby, he was facing appalling agony and danger in order to bring new life into the world.

The epistle of 1 John and the Gospel of John – whether or not they had a common author - agree on the centrality of birth as a metaphor for the cross. In John’s account of the crucifixion, in John 19:31-37, there is unmistakable emphasis given to the observation that there was not just blood flowing from Jesus’ body, but water and blood. And so, today’s reading from 1 John 5 also emphasises. Water AND blood.

Blood and water. This is not just about sacrifice but also about birth; not just death but also new life. Not just cleansing but also recreation.

This is why we always add water to the communion wine.

Birth was the central metaphor for Jesus and so, Jesus indicates, it is for his disciples. They were about to watch him suffer and die and for them, and that will also be like going through labour. For them, there will also be fear, there will be pain, there will be danger. There will be hope - but not certainty - that good can come from all this.

And so, for them, Easter morning was like hearing that first cry from a healthy newborn; like the first sight of a tired but healthy mother holding a healthy baby in her arms. It is OK. The pain and the fear were all worthwhile. Now we can celebrate.

At Easter we sing, in the words of Handel’s Messiah:

The kingdom of this world

Is become the kingdom of our Lord,

And of His Christ, and of His Christ;

And He shall reign for ever and ever.

And so we believe. But what does that mean? When we look around, where do we see Christ reigning in this world?

On the cross, Jesus had a sign above his head that read “King of the Jews”. It was meant ironically, of course, but we believe he is king – that he was king, not just on Sunday bot on Friday as well.

Jesus was king on the cross as well as outside the empty tomb. In pain, in fear, in danger, he was enacting his kingdom. He was bringing new life – new creation – into the world with blood and water. His kingdom was not established with a sword or with a bomb. Not even with a ballot box. But in the pain and fear and danger of childbirth.

And as it was with him, so it is for his followers. His kingdom does not always look like victory and triumph and celebration. Sometimes – often – it looks like pain and fear and danger.

In John this is the primary metaphor Jesus used for his work on the cross and in the tomb. But it is not a metaphor to be put aside after Easter, because Jesus also calls his followers to join him in bringing new life into the world. In John 7:38 he said that out of the believer’s womb life will keep flowing into the world.

Of course, the work of Jesus on the cross and in the tomb was once for all and unique for all time, but it was also a work into which he has called us to participate.

There is a sense in which the church is constantly in labour; constantly engaged in the work of bringing new life into the world. And that is why, although we have been living in post-Easter celebration for nearly 2,000 years, we also experience pain, fear and danger, and the hope without certainly that accompanies labour.

Sometimes we are more aware of this than at others. Sometimes we feel the joy and other times we feel only the pain and the fear. Sometimes we feel certain that our labour is leading towards a beautiful new life, and other times we lose hope and just want the pain to stop, and don’t care how that might happen.

Right now, I suggest our world, and the church in our world, is enduring a time in which the pain and the fear is a far greater reality than the expectation of joy.

We are aware of wars in various parts of the world for which all our simple solutions have fallen short. We don’t know what to do and we can’t even work out what should be done.

Those conflicts that are elsewhere have crossed seas and borders and are being felt in Australia as people take sides and as we see hatred rising again toward both Jews and Muslims.

But it isn’t just inter-racial and international conflict that troubles us. Family and intimate partner violence continues to increase in Australia. In spite of all we have tried to do over the last few decades, increasing numbers of women are dying in this way this year.

Both of those causes of pain and fear are being fed by social media billionaires with no regard for the trauma that their violent and polarising messages are creating in the world.

And all the while polar ice keeps melting and precious species keep falling into the silence of extinction.

And the church in Western countries like Australia is so depleted and divided as to be in no position to meet any of these crises.

What is the church to do? What is the church to say? We don’t know. But if we think of these troubles as labour pains, then we can face them with some hope. We can choose to be midwives to our labouring world. Through prayer, lament and vigil we can be present in the pain, encouraging our world to keep breathing through the pain.

We have the great privilege of living through a time of such significance. We didn’t ask for this, but we can’t refuse the challenge of our times any more than a woman nine months pregnant can refuse to go into labour.

That is our calling: To feel the pain; To experience the fear; To face the danger; And to believe, in spite of it all, that there is new life on its way.

As the church, we are called to be women in labour for the life of our world. And we are also called to be midwives for each other and for a world that has lost hope that there will be anything to celebrate on the other side of such a long hard labour.

This is what Jesus meant when he called us to love one another as he has loved us. Not the feeble love of a besotted youth but the fierce love of a mother, willing to face any pain and danger; willing to give her own life if necessary in order to bring new life into the world. Amen.

You can find a more thorough treatment of birth imagery on John’s Gospel in this post:

Her Hour Has Come

This is a paper I presented at the Fellowship of Biblical Scholars conference in Sydney in September 2023.My usual post are poems, prayers or preaching. If you would like to receive these, add your email address here: Abstract The centrality of birth imagery is a secret hidden in plain sight in the Fourth Gospel. From the very beginning, the author declar…

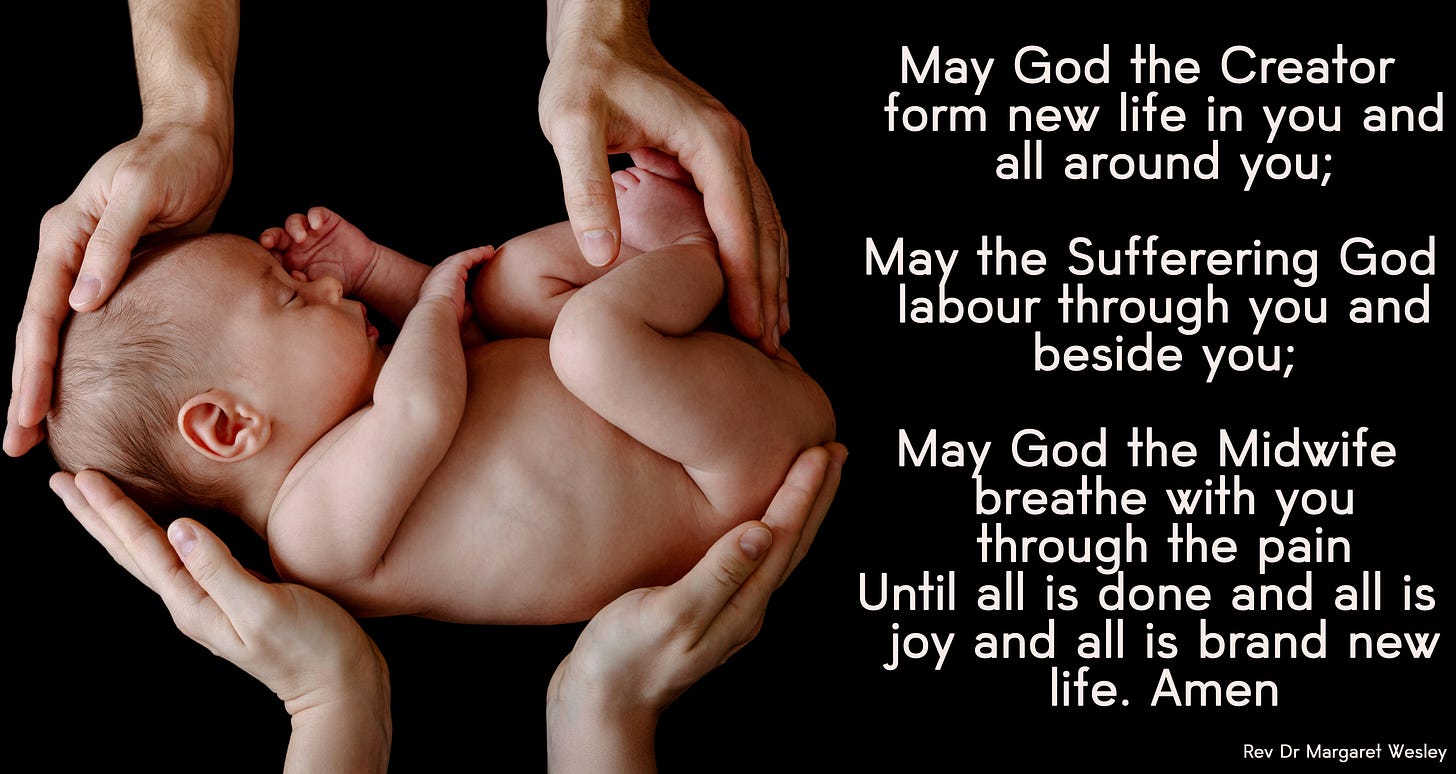

Let’s pray:

With Love from Rev Margaret