The Stones Will Call Out

A sermon on Luke 19:28-40 for Palm Sunday, 2025, Preached at St Paul's, Ashgrove

Today we celebrate the entry of a contested king

into a city that his followers probably believe he is destined to rule,

but where a foreign army holds the power

And any aspiration to local sovereignty will be met with lethal force.

Questions about sovereignty and political legitimacy have come to the forefront of our thinking over the last few years, however much we might prefer not to think about such things. They have been fraught issues in Australia and New Zealand for two and a half centuries, and in the rest of the world Ukraine and Palestine continue to struggle to assert their right to exist, while an increasingly chaotic United States has been throwing out threats to the sovereignty of several nations. In 2025 the current state of Israel, cannot now be spoken of without a shudder of horror over the war crimes being committed by its government – actions that (we must keep remembering) are not supported by the majority of Jewish people.

This is where Palm Sunday finds us this year as we are reminded again about a carpenter from hicksville marching into Jerusalem like he owned the place. We bring a new perspective to this story each year, as our experience in the world changes, and each year we find the perspective of the first readers enlightening.

Luke’s Gospel was written within living memory of the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans. The Christian movement was at that time maybe half/half Jew and Gentile, so for many of the first readers it was their spiritual home that had been destroyed - their emotional base that had been crushed – the centre of their universe that had been flattened. So, they are not unlike the many refugees we see in so many places around the world today – grieving all that has been lost and fearful for the future. They had abandoned all hope for their homeland. There had been hope, there had been a strong defence, there had been a long siege, but it had ended in abject defeat.

Those people would have been in Luke’s mind as he wrote, so, let’s sit with them for a moment and wonder what comfort there might be in this story for those Jewish refugees.

“As Jesus saw Jerusalem, he wept over it.” As the refugees weep, they are reminded that their Lord wept for them before their troubles started. Jesus shows an awareness in advance that Jerusalem will be destroyed, and though he is fiercely critical of the leaders and authorities in Jerusalem, he loves the place and the people. He doesn’t say, “serves them right”. He weeps for them. He understands the grief of these refugees and he joins them in mourning.

Another comfort would come from the Psalm that was sung for Jesus as he approached Jerusalem. “Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord.” This was a big claim to make about Jesus. Psalm 118 was probably a liturgy used to welcome back a king with his army after they had won a victory over a particularly formidable enemy. Jesus had led no army but had achieved victory over the most formidable of enemies – sickness, death, spiritual oppression, ignorance. People mourning over a horrific military defeat are reminded that all is not lost. A great victory has been won, even in the rubble of defeat. Perhaps there are more important victories than military ones.

And perhaps military defeat is no indication of rejection by God. The same Psalm that was sung includes the words: “The stone that the builder rejected has become the corner stone.” The pile of rubble that Jerusalem had become was no indication of its importance to God. This is where God had been praised and God’s guidance sought for centuries and this is where the great work of God was about to be done: The death and resurrection of God’s own loved son – and a path made there for all of us from death to life.

So, for the refugees from defeated Jerusalem, this scene shows that:

Their Lord grieves with them in their grief

There are more important victories than military ones (or political or economic ones, for that matter)

And defeat is no indication of rejection by God.

There is solid comfort in this for those who feel as though they have lost everything. The comfort doesn’t deny the tension, though.

Some of the Pharisees in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, order your disciples to stop.” Stop carrying on about Jesus being a victorious king.

If you are thinking that Pharisees are always the enemy, then you might assume they thought the disciples were wrong. Perhaps they thought it was blasphemy. But there is no indication of that here.

These Pharisees

were part of the crowd that had gathered to welcome Jesus into Jerusalem;

they were close enough to speak to Jesus and be heard above the noise of the crowd; and

they call him teacher.

Put those things together and it is more likely that these Pharisees were friends of Jesus – maybe they were even his followers. Jesus was highly critical of the authorities in Jerusalem, but there would certainly have been a lot of ordinary Pharisees among his followers.

They are reminding Jesus that he is in Roman occupied territory, and surrounded by people claiming – loudly – that he is king. The Roman Emperor and his representatives did not take kindly to people claiming to be king. This was an extremely dangerous thing to do. Possibly a very foolish thing to do. These Pharisees are rightly frightened of the likely consequences of what the disciples are doing.

Let’s think about how those Jewish refugees – among the first readers - would have read that. The world they were living in was becoming anti-Semitic. There had been a deliberate imperial policy since the emperor Claudius of slurring and blaming Jews for all sorts of things they had not done. They had been a small nation for a long time, a weak nation, a subdued nation. Now they were not even a nation at all. They were a displaced people with about as much power as a Palestinian shopkeeper from Gaza today.

They would have been tempted to shut up about who they were – to deny that they were Jews. Christians at this time were often caught up in the hostility against Jews, because Jesus was a Jew and Christians looked like a Jewish splinter group. Christians had also been targeted and made scapegoats by an emperor – Nero. It would have been tempting to deny being a Christian, even in the first century before systemic persecution of the church had really begun.

There was safety in silence. There is often safety in silence. For a while. Those who benefit from violence and war don’t like to hear about the triumph of gentleness and peace. And the people who benefit from violence are the ones with the weapons.

So perhaps it is safer to tone down the enthusiasm.

But what does Jesus say? “If they were silent the stones would shout.” There is no keeping this truth silent. The stones can’t be ordered to keep quiet:

The stones that had been rejected but are now central to God’s design. They will praise their maker! Nobody can stop them!

The stones that Jesus had refused to turn into bread at the beginning of his ministry when he was tempted in the wilderness – because his Father had called them to be stones. They will praise the prince of peace. All parts of creation sing God’s praises simply by being what God made them to be. Nobody can stop them!

Even those stones of the devastated Jerusalem, mourned for by the refugees – those stones that had been beautiful buildings but were now left scattered on the ground, not one upon another – even they will praise the one who sees their devastation in advance and weeps with them. The stones of cities flattened by violence will always cry out to God for mercy and justice. And whenever we cry to God for mercy and justice we are praising God for being merciful and just.

Jesus doesn’t choose the safe path of silence. He knows he’s not called to a life of safety. And because the good news he brings is so liberating and comforting to those who need to hear it, silence is not an option.

And the people of the early church - living in the wake of Jerusalem’s destruction – are called to be living stones, built into a new and living temple, who shout his praises through all the world. Not a safe calling, but a true one.

We are all called to speak this Good News to people who want to hear it and to people who don’t.

Good News about the Lord who grieves with us in our grief

Good news of the ultimate triumph of life over death and peace over violence even while we still see hostile powers experiencing temporary military victory.

And Good News that being defeated by those personal or international bullies is no indication of rejection by God. The rejected ones are the ones God chooses.

This is the Good News we bring to mind as we reflect on Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem and as we enter Holy week.

And so, we are left to ponder Jesus’ challenge as he wept over Jerusalem: “If only you had recognised the things that make for peace!” We can sit back and criticise Jerusalem for not recognising the Prince of Peace when he turned up on their doorstep. Or we can take an honest look at our own lives and our own world and admit that we too have a great deal of trouble recognising the things that make for peace. And once we recognise them, we have trouble acting on them.

What are the things that make for peace?

I invite you to reflect on this over the coming week. Don’t rush to easy answers, but as we move through holy week, let’s be open to God’s wisdom while we grieve the absence of peace in our world, in our country and in our lives. What are the things that make for peace? And how might we do better at embracing those things?

And in your pondering, may the Lord be with you.

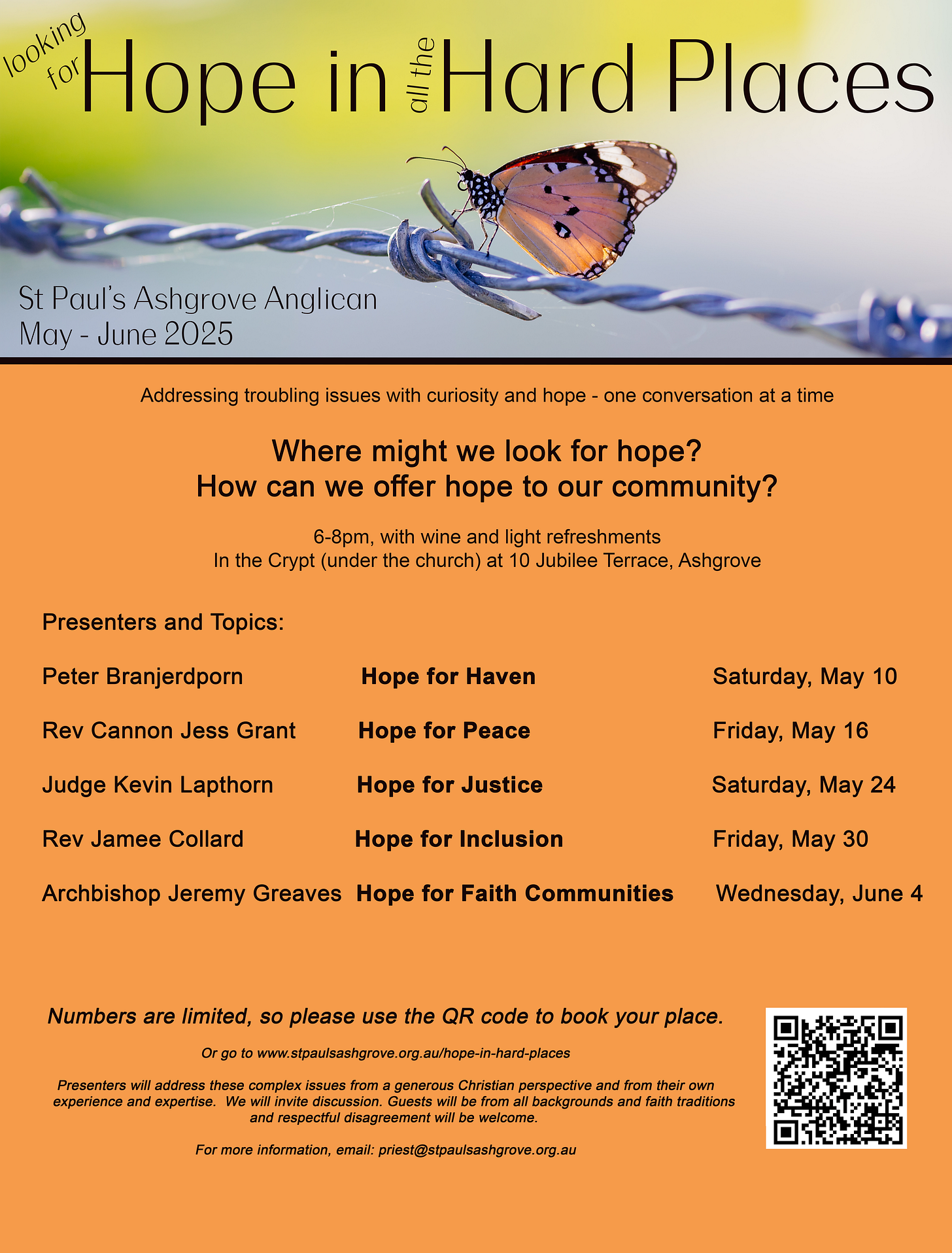

If you are in Brisbane in May-June 2025 we’d love you to join us in pondering such questions:

With Love from Rev Margaret